Jessikka Aro echoes the Smolensk conspiracy. How did she get upon this false lead?

Sometime eight years ago a meeting with Michał Rachoń encouraged a Finnish journalist to set her eyes on what happened in Smolensk. In her new book, the arguments she presents, although commonly known, are questionable; her discussion points although presented in a refreshed tone, repeat debunked allegations. We have reviewed some key claims of this publication.

fot. Maria Mitrunen / Wikimedia Commons / Tekijänoikeuslain 25 § / Modyfikacje: Demagog, fot. Estonian Foreign Ministry / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY 2.0 / Modyfikacje: Demagog

Jessikka Aro echoes the Smolensk conspiracy. How did she get upon this false lead?

Sometime eight years ago a meeting with Michał Rachoń encouraged a Finnish journalist to set her eyes on what happened in Smolensk. In her new book, the arguments she presents, although commonly known, are questionable; her discussion points although presented in a refreshed tone, repeat debunked allegations. We have reviewed some key claims of this publication.

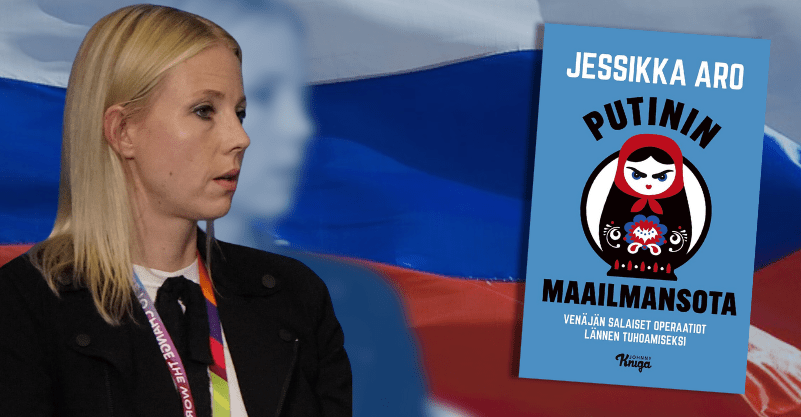

For several years, Jessikka Aro has been investigating Russian disinformation (1, 2, 3). Her publications on the subject, notably the Putin’s Trolls story, brought her fame and recognition, but also made her a Russian target. The Kremlin launched a smear campaign against her, spreading lies, labeling her insane and above all an American spy. Along that, a fabricated story about her surfaced, alleging her involvement in drug trafficking.

As a result of these rumours Aro had to flee from Finland for her safety (1, 2). Those involved in this slander campaign were convicted in 2018.

Currently, the new book by the Finnish journalist – “Putin’s World War” – is on its way to be published in Poland by a company whose board member is Michal Rachon – a journalist for Telewizja Republika. The reason for this may be connected to Aro’s assertion that an explosion could have been responsible for the assassination of the crew and passengers aboard the flight near Smolensk on April 10, 2010.

Beware of the false claims regarding the Smolensk crash

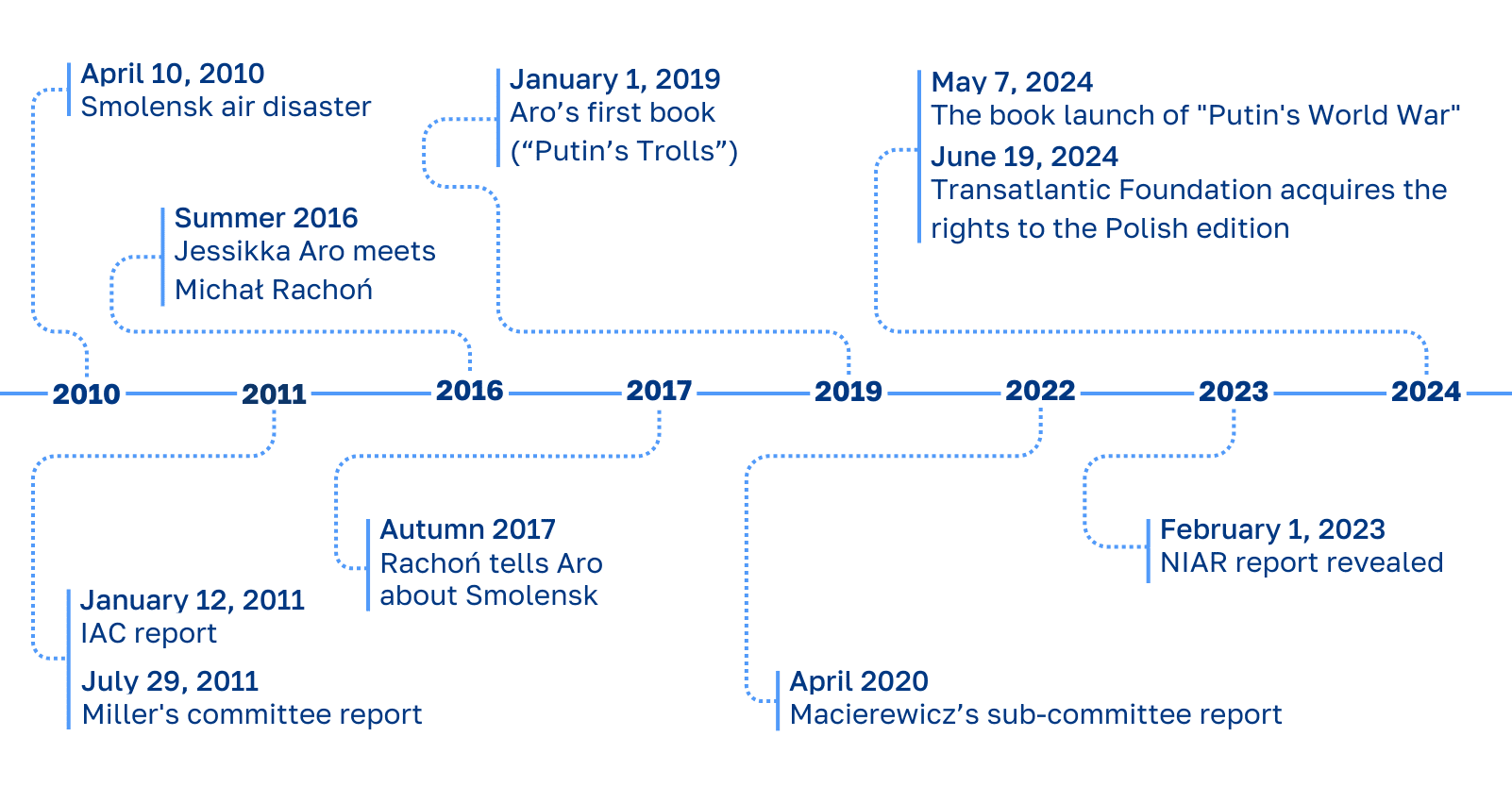

The book was released to Finnish readers in spring of this year. Two months later, in July, the rights to publish it in Poland were acquired by Transatlantic Foundation, a newly established company that is yet to publish any books and does not even have a website.

The Transatlantic Foundation was founded in May 2024. Its two shareholders are Michał Rachoń and historian Sławomir Cenckiewicz. The company was registered on May 7th—the same day Jessikka Aro’s book was released in Finland. At this point, it is worth mentioning that during the Law and Justice party government, Rachoń was a journalist at TVP Info, a state-run TV station whose bias and uncritical allegiance to the government were criticized for the last 8 years (e.g., 1, 2, 3, 4, 5)

The release date of the Polish version is not yet known; however, we are aware that the book contains false information regarding the Smolensk disaster. For this reason, we are publishing our article now, believing it is better to warn against misinformation than to correct it after it has already been disseminated (1, 2).

In the preparation of the following analysis, we utilized the Finnish edition of “Putin’s Global War”. To ensure a thorough and accurate investigation of the matter, the sections concerning the Smolensk disaster were translated for us by a professional translator.

Who did Jessikka Aro speak with?

The book begins with the story of Jessikka Aro’s meeting with Michał Rachoń, whom she met at a conference in 2016. Soon after, the Finnish journalist was persuaded by the Polish TV commentator that a proper investigation into the Smolensk disaster had never been conducted (p. 5).

Michał Rachoń is one of the individuals whose perspective Aro includes in her book. Additionally, the book presents the views of Glenn Jørgensen, a subcommittee member set up by Antoni Macierewicz to re-examine the Smolensk disaster.

The book also offers insights from other individuals, including Marek Pyza, a journalist from wPolityce.pl; journalist Ewa Stankiewicz; Mateusz Kochanowski, the son of Janusz Kochanowski (the former Ombudsman, who died in the Smolensk crash); and Grzegorz Januszko, the father of one of the victims, a flight attendant.

The Smolensk conspiracy theory was not verified by any reports

In “Putin’s World War”, the limelight is shed on the witnesses involved in the investigation rather than an analysis of the investigation itself. The contents of the book do not include a detailed analysis of the reports from various inquiries: the Russian IAC (Interstate Aviation Committee) commission, the Miller commission, the Macierewicz subcommittee, or NIAR (National Institute for Aviation Research).

The journalist also drew on information from the website smolenskcrash.eu, which has not been updated with new content since 2019.

The publication presents only one perspective—that of the proponents of the explosion theory—without offering any critical examination of the outlined arguments.

The three incorrect hypothesis

The book brings three main claims to the forefront, all of which require verification:

- Donald Tusk’s government neglected the investigation and uncritically acknowledged Russia’s narrative.

- The Smolensk airplane crash was caused by an explosion onboard a TU-154M aircraft.

- The Polish perspective is neglected in other countries, being dominated by the Russian version of events.

We will examine these claims one by one, but first, we shall begin by revisiting the basic facts.

Chronological account of the plane crash

On April 10, 2010, at 8:46 AM Polish time, a disaster occurred near Smolensk-Sieverny airfield. A TU-154M aircraft crashed, carrying members of a Polish delegation en route to ceremonies commemorating the Katyn massacre (1, 2). Among the 96 victims were President Lech Kaczyński and his wife, Maria Kaczyńska, Ryszard Kaczorowski (former president of Poland in exile), Tadeusz Buk (commander of the Polish land forces), and Anna Walentynowicz (founder of the Free Trade Unions).

This tragedy is undeniably one of the most significant events in the latest history of Poland. People demanded answers, and in such situations, waiting for the results of a lengthy and meticulous investigation proves difficult.

Shortly after the disaster, amid an atmosphere of informational chaos, a hypothesis emerged that the crash in Smolensk was the result of an attack (1, 2, 3). At that time, no evidence had yet come to light.

It was an accident – two reports confirm

In the first year following the incident, two teams conducted thorough investigations into the crash—one led by Russians, monitored by Polish officials, and the other composed solely of Poles. Both teams reached the same clear conclusion: it was an accident.

The reports differed in the extent to which they attributed responsibility to the aircraft’s crew and the Russian air traffic controllers. However, the authors of both documents agreed on one key fact: the event in Smolensk was an aviation disaster, not an attack.

According to the findings of the International Aviation Committee (IAC):

“The immediate cause of the accident was the failure of the crew to take a timely decision to proceed to an alternate airdrome although they were numerous times timely informed on the actual weather conditions at Smolensk “Severny” Airdrome that were significantly lower than the established airdrome minima; descent without visual contact with ground references to an altitude much lower than minimum descent altitude for go around (100 m) in order to establish visual flight as well as no reaction to the numerous TAWS warnings which led to controlled flight into terrain, aircraft destruction and death of the crew and passengers.”

These findings were similar to the ones presented by the Miller Commission:

“The cause of the accident was the descent below the minimum descent altitude, accompanied by an excessive rate of descent, in weather conditions that made visual contact with the ground impossible, and a delayed initiation of the go-around procedure. This resulted in a collision with a terrain obstacle, the detachment of a portion of the left wing along with the aileron, and consequently, the loss of control of the aircraft and its collision with the ground.”

Doubts and uncertainties remain

The IAC report was not well received in Poland. According to a CBOS survey, three-quarters of Poles found it dubious. Another poll revealed that only one in three Poles considered the Polish report (the Miller commission report) to be satisfactory in its results.

Concerns grew that certain aspects of the investigation had been left unresolved (1, 2, 3). Public skepticism was further shaped by a justified distrust of the Russian Federation’s policies. As Aro notes, Russia may stand to benefit from the divisions within Polish society.

Mistakes were also made during the investigation. Examples include numerous unscrupulousness and ambiguities in the identification of the victims’ remains, as well as the leak of their photographs on the internet (1, 2, 3, 4). A significant point of contention remains Russia’s ongoing refusal to return the wreckage of the Tupolev to Poland (1, 2, 3)—a situation that persists to this day.

Reassessment of the case

This atmosphere favored the actions of proponents of the conspiracy theory. In October 2012, the first Smolensk Conference took place, where a group of scientists, led by Prof. Piotr Witakowski, challenged the version of events presented in the official reports. Over the course of the next three conferences, the conspiracy theory was further developed.

Following the 2015 parliamentary elections, the Law and Justice (PiS) party assumed power, and Antoni Macierewicz was appointed Minister of National Defense. One of his key objectives was to re-investigate the Smolensk crash. As a result, the investigation was reopened in February 2016, and a subcommittee was soon established to carry out this task. Many individuals involved in organizing the Smolensk Conferences were appointed to this subcommittee.

Two years later, Macierewicz assumed the role of chairman of the aforementioned subcommittee. In 2022, the final report was released, concluding that an attack occurred in Smolensk, with an explosive device detonating onboard the Tupolev.

However, numerous irregularities in the subcommittee’s work later came to light. These included the selection of experts to fit a predetermined conclusion, lacking in procedural transparency in the investigation, and the deliberate concealment of analyses and evidence that contradicted the explosion theory. The subcommittee was officially dissolved in December 2023.

Theory no.1 : Poland uncritically accepted the Russian version. This is falsehood.

In her book, Jessikka Aro accounts a conversation with Grzegorz Januszko, the father of the flight attendant who perished aboard the Tupolev. This tragic story serves as an opportunity to level accusations against Donald Tusk’s government, criticizing it for inaction and incompetence in the aftermath of the disaster.

The Interstate Aviation Committee (IAC) and its first report

Let us recall that the initial investigation into the disaster was conducted by the Interstate Aviation Committee (IAC), established in 1991 to investigate aviation accidents across 12 former Soviet republics.

This responsibility fell to IAC under Article 26 of the Convention on International Civil Aviation (ICAO), which stipulates that the country where the aircraft accident occurs (in this case, Russia) is responsible for conducting the investigation.

At the same time, the country in which the aircraft is registered (in this case, Poland) has the right to appoint its own observers to the investigation (p. 10). Polish specialists were sent to Smolensk the day after the disaster.

Civilian or state-owned aircraft?

In her critique of the Polish government (p. 31, p. 54), Aro suggests that a better approach than applying the regulations of the Chicago Convention (ICAO) would have been to base the investigation on the 1993 bilateral Polish-Russian agreement on military aviation.

This argument was notably raised in 2012 by Zbigniew Girzyński, a member of the Law and Justice (PiS) party. At the time, Wojciech Nowicki, the Undersecretary of State at the Prime Minister’s Office, explained that using this agreement was not feasible, primarily due to its limitations. Article 11 of the agreement obligates both parties to jointly investigate aviation incidents, but it lacks detailed procedures, expected formats for presenting findings (such as a final report), and mutual rights and obligations.

Moreover, the government’s specially appointed Commission for clarifying the causes and circumstances of the disaster (pol. Zespół do spraw wyjaśnienia opinii publicznej przyczyn i okoliczności katastrofy) clarified that this agreement could have lead to restrictions on access to classified information. Imposing such secrecy would have resulted in even greater confusion and informational chaos.

It is true that the Chicago Convention regulations apply to civil aviation. There was political debate over whether the Smolensk flight should be classified as military or civilian. Ultimately, both the Polish and Russian governments agreed to use the convention, as it provided a more structured framework for the investigative process.

Poland criticised the IAC report

The IAC report was released in January 2011. It is not accurate to claim that the Polish government uncritically acknowledged the findings of the Russian investigation, a notion which appears in Jessikka Aro’s book. Approximately 100 comments and observations were submitted by the Polish team regarding the conclusions presented by IAC.

Moreover, simultaneously to the work of the Russian team investigating the causes and circumstances of the disaster, the Polish State Aviation Accident Investigation Commission (commonly referred to as the Miller Commission) was conducting its own examination of the events. In July 2011, the Commission released (1, 2, 3) a report containing different conclusions from those in the Russian document.

Both the IAC report and the Miller Commission report concluded that the cause of the disaster was errors made by those responsible for flight safety. Interestingly, the Polish report was more comprehensive.

The key difference lay in the factors and circumstances considered to have influenced the disaster. The Russian side did not acknowledge any irregularities on their part, attributing the cause solely to pilot error (p. 207–208). In contrast, the Polish authorities highlighted additional irregularities committed by Russian air traffic controllers, including providing the crew with incorrect information regarding the aircraft’s position relative to the airport, its descent path, and course (p. 318).

Moreover, the Miller Commission report refuted the MAK report’s claim (p. 207) that psychological pressure exerted on the pilots by the commander of the Air Force, General Błasik, was a contributing factor to the disaster (p. 236). Jessikka Aro seems to overlook these discrepancies, asserting in her book that this error was only later corrected by Macierewicz’s subcommittee (p. 115).

Concurrent investigation carried out by the Prosecutor’s Office

Neither the IAC report nor the Miller Commission report identified a responsible individual for the disaster, yet this was not their presupposed task. However, this does not imply that this detail was intentionally covered up, as one might take away from reading Putin’s World War.

On April 10, 2010, the very day of the disaster, the prosecutor’s office initiated its investigation. It is important to emphasize that the involvement of third parties (i.e., a potential attacker) was one of the four hypotheses considered. Until 2016, the investigation was conducted by the Chief Military Prosecutor’s Office, after which it was handed over to Investigative Team No. I of the National Prosecutor’s Office.

Additionally, in 2014, the prosecutor’s office confirmed that, contrary to Russian claims, General Błasik was not intoxicated on the day of the disaster. Jessikka Aro argues that this conclusion was only presented by Macierewicz’s subcommittee, thereby lacking in the reliability of the argument (p. 115).

Prosecutor’s Office narrows down the list of suspects

As of today, available information indicates towards that three suspects have been identified in connection with the air disaster that resulted in numerous fatalities. These individuals were: Lieutenant Colonel Paweł P. and two Russian officers, for whom arrest warrants have been issued.

It is important to clarify, contrary to suggestions made by Jessikka Aro in her book, that the Smolensk case has not been silenced following the 2023 Polish parliamentary elections. The investigation remains active under the National Prosecutor’s Office. The investigative team is led by Krzysztof Schwartz, who was appointed during the tenure of Minister Zbigniew Ziobro (minister of justice in the PiS government).

Schwartz, who does not endorse the conspiracy theory, has not been removed from his position. He continues his work, and in April 2024, his investigative team met with the families of the disaster victims.

Unknown status of the aircraft wreckage – Poland pressures for retrieval

It is indeed true that Russia has yet to return the wreckage of the Tu-154M to Poland. This situation clearly reflects the Kremlin’s ill intentions, which have exacerbated the political dispute surrounding Smolensk. However, contrary to the implications raised by Jessikka Aro, this delay does not indicate a lack of seriousness on the part of the Polish authorities regarding the investigation.

The Polish government has actively pursued the recovery of the wreckage. During the tenure of the PO-PSL coalition, 11 diplomatic note verbale were sent demanding its return. Efforts were also made during diplomatic meetings to secure its repatriation. The subsequent PiS government has continued these initiatives, although they have not yielded success.

Against Aro’s suggestion that the Russian narrative has gained traction in the Western mainstream, European institutions have remained aware of the irregularities on Russia’s part. In 2018, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe passed a resolution urging the Russian Federation to return the Tu-154M. Additionally, in 2015, the European Parliament called for the return of both the wreckage and the black boxes.

Theory no.2: An explosion occurred onboard of the aircraft

Jessikka Aro and her informants assert that the Smolensk disaster on April 10, 2010, was the result of a deliberate explosion aboard the Tu-154M—a theory reiterated multiple times in her book (e.g., pp. 23, 84, 93, 101, 120). However, this assertion directly contradicts the findings of the Polish investigation led by the Miller Commission.

The Miller Commission’s report explicitly refutes the presence of an explosion. In the annex detailing the damage, it is clearly stated that no traces of explosive materials or fuel combustion were found during the examination of the wreckage (p. 25). The thorough investigation of the debris ruled out the possibility of detonation as the cause of the crash.

It is a fact that the aircraft disintegrated into small fragments upon impact, which may raise suspicions of an explosion. However, according to Michał Przybyłowski from the Department of Criminal Procedure and Forensics at Nicolaus Copernicus University in Toruń, such fragmentation is not unusual in aircraft crashes. This phenomenon can occur due to the immense forces involved, particularly when a plane impacts the ground at high speed under unfavorable conditions, as was the case in Smolensk.

Bodies of the victims indicate an explosion? Experts do not confirm that

Doubts have also been raised regarding the examination of the victims’ bodies. In a conversation with Grzegorz Januszko, the father of one of the victims, Jessikka Aro refers to irregularities concerning the burial of those who perished in the disaster. It was only through exhumation it was revealed, that in many cases, that body parts were not placed in the appropriate coffins. This negligence may have been intentionally committed by Russia for its own political interests.

However, Aro’s second thesis—that traces indicating an explosion may have been found on the bodies—is inaccurate (p. 101).

In collaboration with an international team of forensic experts, the Polish prosecutor’s office has obtained nearly 100 opinions regarding the bodies. What conclusion was reached? According to TVN, the prosecutor’s office informed the victims’ families that no injuries indicative of an explosion were found on the bodies.

Explosions heard? Investigators are not so sure about it

The Macierewicz Commission asserted that the explosion on the aircraft is backed by evidence retrieved from the aircraft’s black boxes. At the same time, the Miller Commission was accused of cutting out significant portions of the audio material to debunk this theory. Jessikka Aro aligns herself with others who have expressed concerns regarding the investigation, highlighting errors made by the Polish authorities responsible for analyzing the black box recordings (p. 52).

In the report “The Power of a Lie” (pol. Siła Kłamstwa) by Piotr Świerczek, it is explained that the Macierewicz subcommittee deliberately manipulated the black box material to support the theory of an explosion [time stamp: 52:00]. Experts assert that the original recordings do not contain any sounds of an explosion; instead, they only capture the sound of the aircraft’s impact with a tree.

Aro further claims that the Russians concealed the black boxes (p. 103). However, this assertion is inaccurate. Of the three black boxes that survived the accident, one was sent to Poland—the ATM-QAR recorder, which was produced in Poland and arrived ten days after the disaster. This recording was reviewed at that time (p. 61). The other two black boxes were examined in Russia in the presence of Polish specialists, and Poland received copies of these recordings as well.

Doors proof for the explosion? This is a misleading interpretation

Another argument is presented by Glenn Jørgensen, a member of Antoni Macierewicz’s Smoleńsk subcommittee, concerns the aircraft doors. The Danish engineer points out their weight: more than 75 kg, Jørgensen claims that only high internal pressure, such as that caused by an explosion, could have violently torn the doors off (p. 93).

This assertion is contradicted by the conclusions of the NIAR report. The calculations provided in the report (pp. 205–211) indicate that a sufficiently forceful impact with the ground could also lead to the violent detachment of the doors. It is noteworthy that this report was commissioned by Macierewicz’s subcommittee, making it surprising that Jørgensen fails to present the complete context derived from it.

Jørgensen also questions why there was no crater despite the airplane hitting the ground with great force (p. 97). The team responsible for clarifying public opinion of the information and materials related to the disaster addressed this issue, explaining that the lack of a crater was due to the plane’s tilt upon impact. The aircraft first made contact with the ground using the top of its delicate fuselage, and only later did larger sections of the Tu-154 sustain damage.

The birch tree was a hoax? Evidence suggests otherwise

It is suggested that the crash occurred because the pilots descended too low and failed to initiate a go-around procedure (1, 2). As a result, the aircraft began to descend rapidly, and one of its wings struck a birch tree. This conclusion has faced challenges, with Antoni Macierewicz even proposing to debunk this theory through an experiment involving a moving car and a birch tree.

Jessikka Aro also addresses this issue. In her conversation with Jørgensen, she suggests that Polish pilots did not attempt to land and that the birch did not tear off a piece of the wing (p. 120). However, this assertion is inaccurate. Numerous independent pieces of evidence confirm that the TU-154M collided with the tree.

This evidence includes fragments of the wing found embedded in the birch, as well as pieces of the tree lodged in the wingtip. Additionally, the birch is only one of several trees damaged by the falling aircraft. The incident is further corroborated by recordings from the radio altimeter and a report from a researcher at the University of Toronto, who conducted calculations related to the collision.

What about the traces of the TNT explosive?

Traces of explosives were found on board the TU-154M. This was a significant argument raised by proponents of the explosion theory, which Aro also mentions in her book (p. 57). However, the discovered materials do not confirm the thesis in full.

The conducted studies proved that 90% of the samples with traceable amounts of TNT were found on the spare seats of the aircraft. In the past, this aircraft had been used to transport soldiers, who might have carried residues of such substances on their clothing.

This state of facts is also confirmed by the documentary “The Power of a Lie” — we hear that no TNT was found at all on the left wing [timestamp: 43:28]. And it was precisely there, according to the presented explosion theory, that the explosive charge was supposed to be located. The explosion was ruled out by an examination conducted by the Central Forensic Laboratory of the Police [timestamp: 41:30].

The questionable competencies of a Danish investigator

In “Putin’s World War”, Glenn Jørgensen emerges as the primary advocate of the explosion theory regarding the Smolensk disaster. A Danish engineer who collaborated with the Smoleńsk subcommittee led by Antoni Macierewicz, Jørgensen presents himself as an expert, claiming that his mathematical calculations confirm an explosion aboard the Tupolev. However, his credibility is largely superficial.

In the past, Jørgensen, including in the book (p. 90), claimed to be a lecturer at the Technical University of Denmark. When we contacted the university for clarification, they could not give as an answer aboutthis information. Additionally, the CV available on Jørgensen’s company website does not include this credential, raising further doubts about his qualifications.

Chris Protheroe (1, 2, 3, 4) an expert hired by Macierewicz’s subcommittee, acknowledges that Jørgensen did take a course related to aviation accident investigation. However, it is important to note that Jørgensen enrolled in this course only after joining the Smolensk subcommittee [timestamp: 9:00], which calls into question his prior expertise in the field.

Jørgensen himself admits to speaking on certain issues despite not being an expert. For instance, in *Putin’s World War*, he presents hypotheses about the injuries that the alleged explosion might have left on the bodies of the victims. His conclusions, however, are based on self-study, as he states that “although he is not an expert in medicine, he has familiarized himself with the literature on the injuries caused by explosions” (p. 101).

Jessikka Aro does not challenge his claims by consulting relevant experts, such as forensic medicine specialists, nor does she consider the opinions of those who analyzed the case on behalf of the prosecution. This omission leaves Jørgensen’s assertions unchecked, limiting the objectivity of the arguments presented in her book.

Theory no.3: The Russian narrative is prevalent in the West

In “Putin’s World War”, Jessikka Aro argues that key facts surrounding the Smoleńsk disaster are largely unknown outside of the Polish audience. She implies that the accident theory spread internationally due to the passivity of the Polish government and the ignorance of other countries towards the issue. As Aro contends, “the version of events fabricated by Russia is repeated in respected international media such as Foreign Policy and Wikipedia” (p. 38).

One of the key campaign promises of the Law and Justice (PiS) party was to internationalize the investigation into the Smoleńsk disaster. In response, efforts were made to engage foreign entities. However, Aro criticizes foreign media for allegedly downplaying the results presented by Macierewicz’s subcommittee (p. 84). She expresses surprise that the explosion hypothesis put forward by the subcommittee was largely ignored, while the media continued to rely on the findings of the Miller commission report.

Aro’s perspective overlooks a crucial factor: the composition of Macierewicz’s subcommittee. Unlike the Miller commission, Macierewicz’s team lacked experts with direct experience in investigating aviation accidents. This absence, combined with widespread concerns about the investigation’s politicization and adherence to a pre-established explosion theory, significantly undermined the credibility of the subcommittee’s conclusions. Consequently, it is unsurprising that the foreign media remained skeptical and did not embrace the subcommittee’s findings.

International investigation team

In the re-examination of the Smoleńsk disaster, the physicochemical analysis of samples from the crash site involved collaboration with international institutes from Italy, Northern Ireland, and Great Britain. Additionally, international experts contributed to the work of Antoni Macierewicz’s subcommittee. However, not all participants ultimately agreed with the conclusions reached by the subcommittee. Three former members publicly expressed their dissent by publishing an open letter criticizing the investigative methods employed (1, 2, 3).

One notable case of dissent is that of British aviation accident researcher Chris Protheroe (1, 2, 3, 4). In a recent report, Protheroe admitted his disagreement with the subcommittee’s findings but indicated that he is bound by a confidentiality agreement, limiting what he can disclose. He also revealed that when his research failed to support the explosion theory, his compensation was stopped by the subcommittee [timestamp: 17:00].

Further contradictions arose from the findings of the National Institute for Aviation Research (NIAR), which had been commissioned by the subcommittee. While the NIAR report presented conclusions that conflicted with Macierewicz’s explosion hypothesis, who publicly claimed that the document supported his views. In his investigative report titled “The Power of a Lie,” journalist Piotr Świerczek argued that Macierewicz selectively concealed findings that contradicted his theory and manipulated the report’s results to align with his conclusions.

Meanwhile, the Polish prosecutor’s office, which is conducting an ongoing investigation into the disaster, has assembled an international team of experts. The team’s reports, initially expected by August 2024, are still pending public release. Despite requests for transparency, the prosecutor’s office has declined to provide us with these expert opinions under public information access laws. However, *Newsweek* reported in early October 2024 that the report has already arrived in Poland and is currently being translated into Polish.

Aro’s book lacked in justifications

The conclusion presented to the reader in “Putin’s Global War” is that an explosion occurred aboard the TU-154M. Jessikka Aro gives significant weight to the arguments of Glenn Jørgensen—an individual with no verifiable experience in investigating aviation disasters—and the subcommittee in which he was involved.

However, she seems to overlook or minimize the findings of two key independent Polish investigations: the Miller Commission and the Polish prosecutor’s office. In addition, she disregards the report from the National Institute for Aviation Research (NIAR), which, as previously mentioned, also supports the theory of an accident rather than an explosion.

Aro’s reliance on questionable sources was flagged by Finnish fact-checkers from the organization Faktabaari. They were among the first to scrutinize her work, pointing out the use of unreliable information in her analysis. One of the analysts from Faktabaari, who closely examined Aro’s new book, shared their insights with us:

“In the book and in other contexts, Aro has often stated that the fight against Russia’s influence on information is personally important to her. I greatly appreciate Aro’s work, but in this case that motive may have blinded her to the facts. In addition, the Smolensk conspiracy theory has many hallmarks of cleverly constructed propaganda. It appeals to emotions, contains a lot of seemingly scientific technical evidence, and is ultimately based on the exclusion of real sources and facts”

What can we learn from the book?

In *Putin’s World War*, Jessikka Aro presents a series of loosely connected arguments. While she correctly identifies certain irregularities and inconsistencies in the investigation of the Smolensk disaster, she does not provide concrete, substantiated evidence to support her overarching thesis. Instead, she often highlights suspicious elements or locations without successfully weaving them into a cohesive narrative.

A significant shortcoming of Aro’s approach is her failure to confront or critically compare the statements of her sources with the available evidence and reports from independent investigations. By the time she was working on the book, many of the facts and findings—such as those from the Miller Commission, the prosecutor’s office, and the NIAR report—were already publicly available. Aro’s omission of these well-documented conclusions undermines the credibility of her account, as she overlooks key evidence that contradicts her claims.

One in three Poles is suspicious of the Smolensk catastrophe

In ‘Putin’s World War’, Jessikka Aro concludes that the Smoleńsk disaster has deeply divided Poland—a claim that is undoubtedly true. Surveys conducted over the past 14 years show that belief in a conspiracy or attack surrounding the tragedy has consistently ranged from one-quarter to one-third of the population (1, 2, 3).

For instance, a recent report from the Coalition Together Against Disinformation (pol. Koalicja Razem Przeciwko Dezinformacji) revealed that 29% of Poles currently believe that an attack, rather than an accident, took place in Smoleńsk.

This enduring belief suggests that Aro’s book will likely resonate with a significant portion of readers. However, it is important to recognize that believing in an attack does not necessarily imply belief in the specific theory that an explosion occurred aboard the TU-154M.

Despite this distinction, Aro’s arguments—many of which have already been debunked or thoroughly investigated—may still appeal to those already inclined to believe in the attack hypothesis.

The concern is that Aro’s book, rather than clarifying the situation, could exacerbate the divisions and disinformation that she aims to oppose.

The influence of Russia in stoking the controversy over Smoleńsk is frequently highlighted, as is the idea that Moscow sought to sow discord within Poland. However, Aro’s book omits the role of key Polish figures, particularly from the Law and Justice (PiS) party, who have contributed to the confusion. Antoni Macierewicz and his subcommittee, principally, have persistently pushed the explosion theory, even when faced with contradictory evidence, such as the NIAR report commissioned by Macierewicz himself.

Aro’s informants—like Michał Rachoń and Marek Pyza—are notably aligned with this camp, which has sustained the narrative of an attack despite the available evidence to the contrary. Aro’s omission of these dynamics weakens the broader analysis of the political and social forces at play in Poland, making her book more likely to reinforce existing biases rather than challenge them.

Aro’s book planned to appear in other countries

The translation rights “Putin’s World War” were already granted to six countries, but it is telling that the Czech publisher has withdrawn from the project. This decision was reportedly due to the book’s reiteration of erroneous theses regarding the Smoleńsk disaster.

We believe it is crucial that readers in other countries also have access to the established facts on this matter. To ensure this, we published our article in English and direct readers to the article written by the Finnish fact-checking organization, Faktabaari.

“In Faktabaari, we were really concerned that after the publication of Aro’s book, the conspiracy theory initially spread freely in the Finnish media. This was probably due to the fact that a lot of time has passed since the Smolensk plane crash – and certainly also due to Aro’s position as a well-known journalist. Faktabaari is a small player in the media, but we felt that someone had to take up the case and we knew that it could be clarified by means of fact-checking.”

Aro’s comment awaited

Jessikka Aro has been, and continues to be, a prominent figure in the fight against Russian disinformation. In 2022, she appeared as a guest on our podcast, where she emphasized that alongside the conventional invasion of Ukraine, Russia is also waging an effective information war.

Aro’s previous work is known for its valuable and reliable investigations into Russian disinformation networks. Unfortunately, in the case of the Smoleńsk disaster, it appears that she may not have thoroughly verified her sources.

To gain clarity, we reached out to Aro for a commentary. Specifically, we wanted to know if, during her research for *Putin’s World War*, she had consulted experts who disagree with the conspiracy theory and whether she had reviewed reports whose conclusions conflict with those presented in her book.

As of now, we have not received a response from Jessikka Aro. Should we receive her comments, we will share them accordingly.

*If you find an error, highlight it and enter Ctrl + Enter